Today’s Storms, Tomorrow’s Leaders: Belle Haven Youth on Building Climate Resilience

- Lina Karamali

- Sep 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 19, 2025

By Olivia Johnson, CRC Environmental Storytelling Intern

It takes a village—to raise a child, yes, but also to weather a storm, withstand a heatwave, and speak up when systems fall short. Whether it refers to parenthood or community resilience, the proverb underscores the need for solidarity during hardship. Amid worsening social isolation, the benefits of community—stress reduction, improved sense of belonging, exposure to local resources, and more—have become increasingly important for emotional and physical health. Togetherness isn’t just found in churches or cubicles; for residents of Belle Haven, it’s created through dialogue in their local community center.

Belle Haven is a neighborhood in eastern Menlo Park, originally established by predominantly Black families who were prevented from buying homes in West Menlo Park or Palo Alto. Housing prices in Belle Haven remain substantially lower than in other areas of Menlo Park, but affordability comes with a tradeoff: many homes lack air conditioning units, rely on faulty electrical systems for power, and a lack of tree canopy pushes up temperatures. Consequently, residents are less prepared to manage heat waves, which have increased in magnitude and frequency in recent years. For years, Climate Resilient Communities has sought to address and preempt these issues by helping Belle Haven inhabitants develop adaptation strategies to cope with the effects of extreme weather. But to provide preventative, not just reactive support, requires addressing the root of the crisis.

The Belle Haven Climate Resilience Youth Workshop starts with those who will live with the consequences of our planetary crisis: our children. Taking place on June 20, 2025 in the Belle Haven Community Center, locals gathered to speak to Climate Resilient Communities and partnering organizations about the issues they’ve struggled with as Belle Haven residents and their thoughts about climate change. In doing so, the workshop gave attendees both a forum to express their concerns about community safety and a safe space to discuss more personal observations and anxieties about the state of our natural world.

The workshop began with a presentation from Kamille Lang, Director of Outreach and Education at Climate Resilient Communities. Lang’s words echoed one of the core missions of the environmental coalition: “building community capacity.” Though Climate Resilient Communities works with other organizations to bolster community resources, it’s imperative that civilians feel empowered to create their own systems for social change. Lang emphasized that this meeting was for Belle Haven residents who see issues in their neighborhood and want to help solve them. She then launched into the findings from two community vulnerability assessments conducted in Belle Haven; one with adults, and one with youth. The adult focus group cited flooding and poor housing conditions as two of the main issues, while the struggles of the youth focus group centered around inadequate resource accessibility during extreme weather events. They discussed how they found it difficult to concentrate during periods of extreme heat, demonstrating the multitude of compounding and cascading adverse effects global warming has on social and physical health. Youth also felt a lack of structural support when facing extreme weather conditions, pointing to the fact that there is little public restroom access in parks, limited bike access, and unsafe crosswalks, conditions that are only exacerbated during floods and heat waves. Though the effects of climate change are experienced differently across age and socioeconomic status, the one thing the two focus groups had in common was a desire to become more involved in local mitigation efforts. The workshop prioritized youth attendance, but was open to people of all ages; in framing the workshop this way, Climate Resilient Communities bridged generational gaps in environmental literacy by promoting discourse between community members.

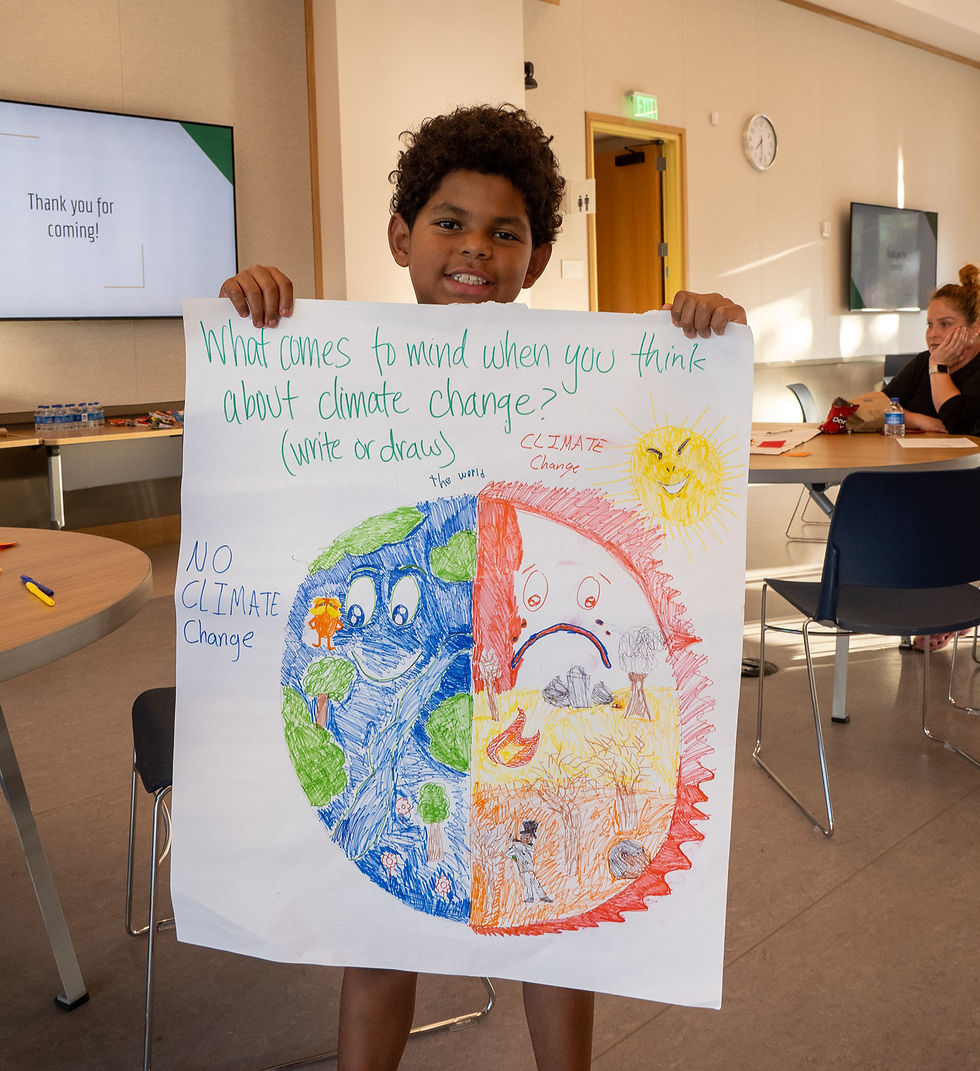

In keeping with themes of collaboration and group discussion, the workshop then pivoted to a brainstorming session, intended to better understand how Belle Haven residents experience climate change in their everyday lives. Attendees were given thirty minutes to respond to the prompt “what comes to mind when you think about climate change?” and add their ideas to a sign. Interns and staff implementing the event then spoke to participants to get a more in-depth understanding of the systemic and economic barriers the community faces to creating resilient homes. The results of these discussions were eye-opening: renters across the board felt that asking their landlords for renovations would cause an increase in rent, while others who sought to install air conditioning units in their homes feared doing so would result in unaffordable PG&E bills. When the six groups presented their posters, the community’s anxieties became apparent.

The first group discussed the adverse effects of wildfires on public health, a common fear amongst Californians, and how floods create physical barriers for East Menlo Park residents that impede plans for mutual support during crisis. Composed mainly of participants in Climate Resilient Communities’s Youth Climate Collective program, the second group pointed out on the effects of climate change on wildlife, citing that the birds and bugs that once populated their bike paths are growing increasingly scarce. The third group expressed a desire for improved transit systems, especially when it comes to taking public transportation to school during heat waves. Narrowing in on the effects of climate change in Belle Haven, the fourth group discussed how power outages—whether they be a result of extreme heat or earthquakes—expose the community’s lack of preparedness when it comes to natural disasters.

Prompted by a question about the tools needed to manage power outages, the group stated that flashlights, power generators, and portable chargers were all necessary. This demonstrates an example of the disconnect between community knowledge and resource access: though Belle Haven residents know what they need, the challenge is ensuring the accessibility of such supplies: one woman discussed how the power was out in her home for nearly a week before someone provided her with a portable charger.

The fifth group, a family of Belle Haven natives, took a more creative approach, drawing a Lorax-inspired picture of the Earth. In the image, half of the Earth is lush with trees and adorned with a happy face, representing what the world could look like in the absence of climate change. Contrastingly, the other half of the world, drawn to depict what Earth could look like if climate change worsens, is engulfed in flames, populated by dead trees and litter. Lastly, the sixth group discussed blustery winds, which can cause both immediate structural damage and exacerbate preexisting problems. The team considered how stronger winds lead to widespread distribution of allergens like pollen, harming public health, and can sweep litter into storm drains, leading to more floods. Their response encapsulates the core struggle of Belle Haven: without adequate support from local officials or the community at large, one hot day or strong storm can introduce a host of issues for residents that impede their health, safety, comfort, and access to educational and professional resources.

Though the findings from this workshop could have been dispiriting, the participants left more intent on combatting these issues. After the group share-outs concluded, Climate Resilient Communities reviewed priority projects and pitched potential solutions to Belle Haven residents. To ensure the audience felt confident in their disaster preparedness skills, Lang asked them if they knew what to do when the power went out and what students could do when it’s flooded and they have to attend school. Encouraging communication between community members not only fosters meaningful connection, but exposes people to novel ways of managing climate stressors. Though participants initially said they didn’t know what to do in the event of a power outage, after a few minutes of discussion, attendees were swapping stories about bringing coolers and ice into their homes to store food and lighting candles in bouts of darkness. Some even exchanged phone numbers so they could connect the next time they found themselves in need.

The workshop made one truth abundantly clear: just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to build resilience—where collective knowledge and shared determination creates a community that not only weathers adversity, but grows stronger from it.

Comments